The Beginnings of a Monastic Separation

Did you know that in the beginning, the sisters of the Hôpital général de Québec monastery were totally dependent on the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec community? The Hôpital général only became a distinct and independent entity in May 1701, eight years after the arrival of the Augustinians. Archivist Audrey Julien retraces the story behind the separation.

Do you know the Saint-Augustin monastery? Founded January 1, 2016, it combined four active Augustinian monasteries: the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, the Hôpital général de Québec, the Hôtel-Dieu de Chicoutimi and the Hôtel-Dieu de Roberval. The four monasteries are now designated as a community. Created with the future in mind, the group reflects the changing needs of religious communities today. The main reason behind its creation was the aging community and decreasing number of members, which has led to management issues of an increasing complexity as time passes.

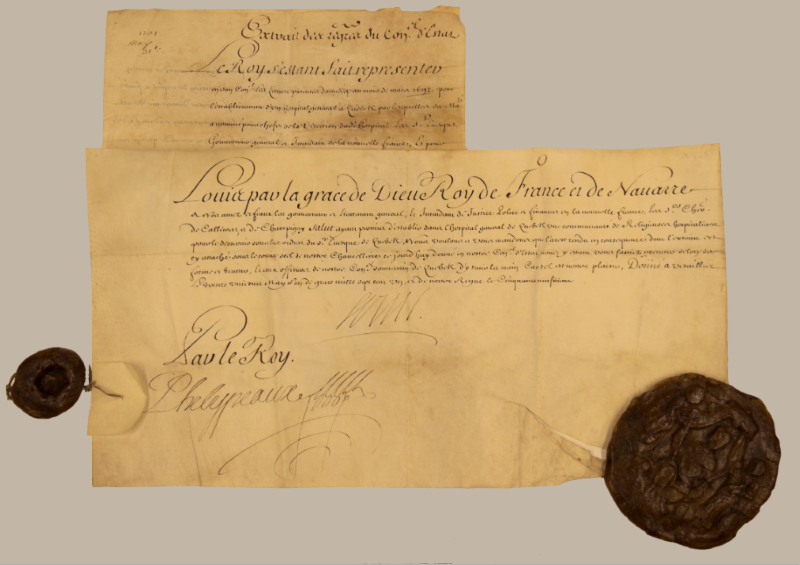

The major reorganization brings to light an obvious fact: for this union to take place, there was an initial separation. The event, which involved the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec and the Hôpital général de Québec, officially took place on May 31, 1701. The date is noted on the letters patent from King Louis XIV that allowed the establishment of a religious community at the Hôpital général de Québec. However, there is a backstory which reveals the events that led to the signing of the document.

Founding a General Hospital

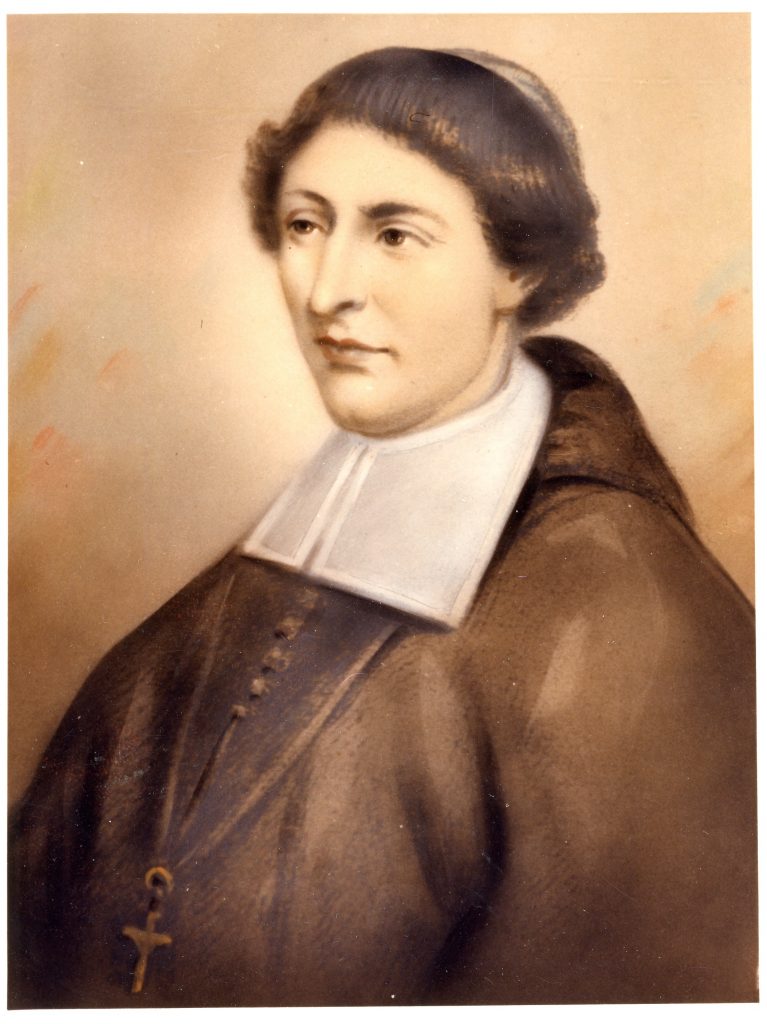

The idea of founding a general hospital to care for elderly and vulnerable people in New France originally sprouted in the mind of Québec’s first bishop, Monseigneur François de Laval. Unfortunately, the circumstances of his time weren’t favourable to establishing it. His successor, Monseigneur Jean-Baptiste de la Croix de Chevrière de Saint Vallier, made it his duty to complete the project upon his arrival in Canada as bishop on August 15, 1688. Many opposed the idea, as there was already a Bureau des pauvres (“office for the poor”) managed by secular administrators charged with redistributing revenue obtained from citizens and communities to people in need. Mgr de Saint-Vallier insisted, however, that he would take the poor invalids in his charge; consequently, the Bureau des pauvres administrators would fall under the jurisdiction of the Hôpital général, thus leading to its closure.

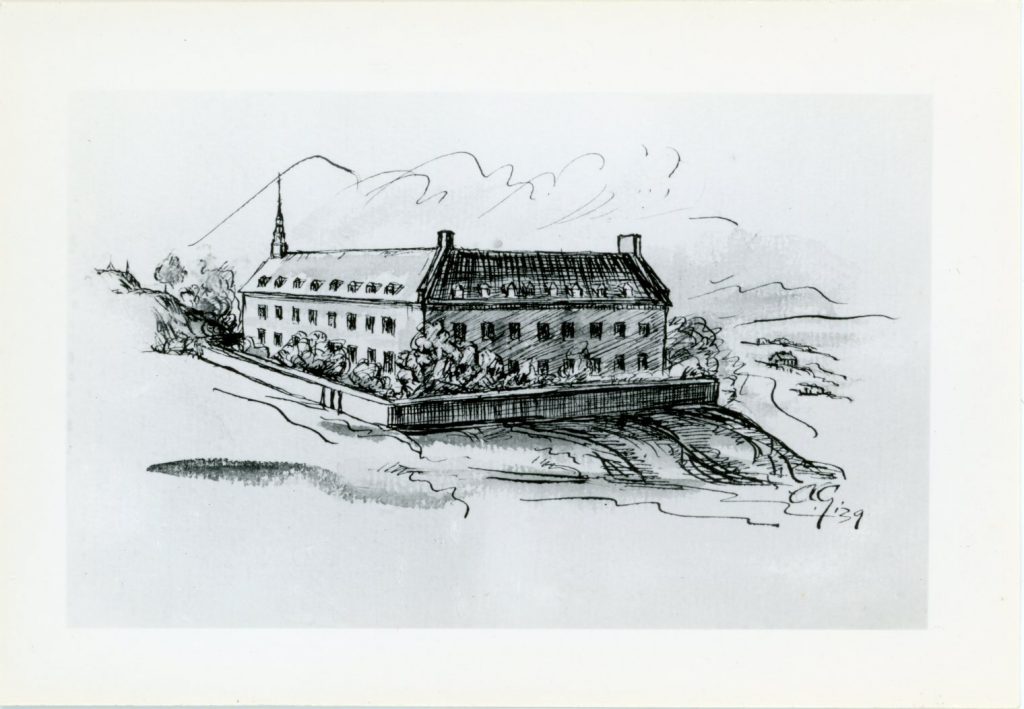

In March 1692, Mgr de Saint-Vallier obtained the letters patent from the king for the establishment of a general hospital. On September 13 of the same year, he completed the purchase of the Récollets convent, located not far from Québec on the banks of the Saint-Charles river. He called on the Notre-Dame Congregation to care for the poor, and, on October 30, he welcomed them under the leadership of Sister Ursule and widow lady Denis.

To ensure the project’s longevity, Mgr de Saint-Vallier wished that active, knowing and devoted women take charge of watching the interns and dealing with the details of the domestic economy. He therefore looked to the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec’s nursing sisters, who first refused his request. They feared a possible change in their way of life, and losing several good subjects to caring for the sick. Rather, they suggested that Mgr de Saint-Vallier invest the funds destined to founding the establishment to build rooms attached to l’Hôtel-Dieu where they could welcome invalids. According to their rule, they could not abandon the sick to care for invalids.

The last point did not suit the Québec bishop. He reiterated his request to the nursing sisters with a renewed confidence despite the opposition of the Hôpital général’s administrators. The Hôtel-Dieu finally gave in under the advice of its administrators to appease tensions and avoid tarnishing the image of their house: “Monseigneur asked us for four sisters, and we obliged to give them to him, and to replace them when one of the four dies” (Hôtel-Dieu de Québec annals 1636-1716). On April 1, 1693, the four founders bid farewell to their community, not without tears and apprehension due to the challenge which awaited beyond the walls of the cloister where they had taken their solemn vows.

The contract signed between the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec sisters and Mgr de Saint-Vallier stipulated that the Hôpital général sisters were dependant on the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec. After a two-year trial, Mgr de Saint-Vallier decided that it would be preferable to elect a superior at the Hôpital général and that the 1000 francs granted by him be managed by the sisters of said hospital. In addition, the four founders were not sufficient to fill the Hôpital général’s growing needs, and the prelate made several requests to add Hôtel-Dieu sisters to his mission. Between 1696 and 1699, the Hôtel-Dieu consented to part with three more of its girls. Despite herself, newly arrived Sister Catherine Thibierge de Saint-Joachim became the turning point of the story. From the day after her arrival at the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, the rumour that Mgr de Saint-Vallier had brought the young sister by force to the Hôpital général spread around the city. Despite the young girl’s attempts to dismiss these lies, people succeeded in convincing her family to make her go back to the Hôtel-Dieu as a question of honour.

The Starting Point of the Separation

The prelate could no longer stand all the agitation, and decided to take things into his own hands. On March 12, 1699, Mgr de Saint-Vallier paid a visit to the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec with the following order:

« We order that from this day forth, your two houses remain separate, and that they each be led by their superior in the regular way of the other communities in France who have the power to make their elections and admit novices to the task and profession […] as much for the past as for the future […]” (Order from Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier for the separation of the Hôpital général and the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec).[1]

The order was signed on April 7 by the sisters of the Hôtel-Dieu “although against our will and sentiment but only to yield to authority and to the major power” (Election of the superior on March 12, 1694). The Hôtel-Dieu sisters however presented a few articles which were applied to the order, including the limitation of the number of Hôpital général sisters to 15, while allowing the admission of secular women to help them. For the Hôtel-Dieu sisters, the reasoning behind this article was that “the two houses are too close to one another to be able to find subjects to fill them both because of the small number of inhabitants, and that if the two houses cannot subsist, the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec house is more necessary than that of the Hôpital général and that finally, the young women come much more willingly for the Hôpital général than for the Hôtel-Dieu because they are less exposed to death, there are fewer charges, the air and the situation are more pleasant, and there is the appeal of novelty” (Articles presented to Monseigneur)[2].

The order was a deliverance for the Hôpital général sisters, who felt comfortable again and devoted themselves with renewed fervour to their nursing duties: “They however did not ignore that their sisters from Québec only saw the new order of things with sorrow. Certain poorly contained rumours, certain mysterious words reached their ears and gave them enough to hear that something unfortunate was afoot in the shadows, and that there were secret pursuits in France” (Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier et l’Hôpital général de Québec, p. 139)[3]. The Hôpital général sisters, who since had admitted novices to their monastery, prepared to have them profess. The Hôtel-Dieu sisters pleaded with them to await the reply from Court. Nonetheless, Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier presided over the profession ceremony on July 31, 1700.

| ©Monastère des Augustines Archives

Risking Dissolution

In September 1700, the king’s ship docked with bad news on board. In a letter written on May 5, 1700, the king ordered the complete dissolution of the Hôpital général community. From then on, it would be solely managed by secular administrators. The Hôtel-Dieu sisters were surprised by these radical measures, having only suggested limiting the number of young girls admitted to the Hôpital général monastery. The king ordered the sisters’ return to the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, but the community refused to accept the sisters who had made their profession at the Hôpital général, knowing welcoming them could disturb the peace.

Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier left for France on October 13, 1700 to support and defend the Hôpital général’s interests, which were being so gravely compromised. Here is an example of the points that Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier defended in Court regarding the necessity of making the Hôpital général an independent monastery:

- Without the separation, peace will not be achievable between the different parties, as it seems impossible to agree upon the number of sisters to allow for the Hôpital général;

- We cannot entrust the care for the general hospital to secular women and widows, as their number is insufficient in New France;

- The Hôpital général was led with much success and edification in the management of both the temporal and spiritual aspects;

- Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier would be forced to withdraw the funds he had allocated to the Hôpital général if the nursing sisters were no longer to be its guardians.

These arguments finally convinced the king, who had letters patent written on May 31, 1701 allowing the establishment of the Hôpital général de Québec community.

Coming Together for the Future

This story helps us draw parallels between the past and the present. Today, we recognize that one of the reasons that triggered the creation of the Saint-Augustin monastery is the aging community and its decreasing number of members. 318 years prior, the reverse was true: the growing religious community and needs of the population led to the separation between the founding monastery, the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, and its first foundation, the Hôpital général. For the sisters who experienced it, the separation was very painful. But thanks to Mgr de Saint-Vallier’s determination and devotion, as well as the generosity and openness of the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec’s sisters, the Augustinians gave birth to a total of 12 hospital monasteries throughout Québec and three missions abroad, all the while helping create a strong and united Canadian federation.

Further reading

OURY, Guy-Marie. Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier et ses pauvres 1653-1727, Les Éditions La Liberté, Québec, 1993, 185 pages.

O’REILLY, Sister Hélène. Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier et l’Hôpital Général de Québec, C. Darveau Imprimeur-Éditeur, 1882, 743 pages.

JUCHEREAU de St-Ignace, Mother Jeanne-Françoise et Marie-Andrée DUPLESSIS de Sainte-Hélène. Les Annales de l’Hotel-Dieu de Québec 1636-1716, Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, Québec, 1984, 444 pages.

[1] « Nous ordonnons que dez ce jour à l’avenir vos deux maisons demeureront séparées, et qu’elles seront conduites chacune par sa supérieure en la manière ordinaire des autres communautés de France qui ont pouvoir de faire leurs élections et d’admettre des novices à l’épreuve et à la profession […] tant pour le passé que pour l’avenir […] » (Ordonnance de Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier pour la séparation de l’Hôpital Général de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec).

[2] « [Les] deux maisons sont trop près l’une de l’autre pour pouvoir trouver des sujets pour les remplir toutes deux attendu le petit nombre d’habitants, que si l’une et l’autre maison ne peut pas subsister celle de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec est plus nécessaire que celle de l’Hôpital Général et que finalement, les jeunes filles se présentent beaucoup plus volontiers pour l’Hôpital Général que pour l’Hôtel-Dieu attendu qu’elles y sont moins exposées à la mort, qu’il y a moins de charge, que l’air et la situation y sont plus agréables et l’attrait de la nouveauté » (Articles présentés à Monseigneur).

[3] « Elles n’ignoraient pas néanmoins que leurs soeurs de Québec ne voyaient qu’avec peine le nouvel ordre des choses. Certaines rumeurs mal contenues, certaines paroles mystérieuses parvenaient à leurs oreilles et leur donnaient assez à entendre que quelque chose de fâcheux se tramait dans l’ombre, et qu’il se faisait des poursuites secrètes du côté de la France » (Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier et l’Hôpital Général de Québec, p. 139).